Numbers and Nerd Stuff

While we’ve been lazing around on the beaches in Aruba, I decided to put together some nerd stuff – numbers, mileages, averages, and other dorky data – as well as some other interesting miscellaneous notes about the trail. At least we find it interesting. Before the numbers, some explanation about total PCT miles, reroutes, and alternate trails:

Distance of the PCT

Before we can really get into the numbers, a few quick notes on the total distance of the PCT, since many of the figures below are based on this number. The official distance of the full trail, from the Mexico to Canada borders, comes in right around 2,650 miles, varying slightly each year as the trail morphs with minor detours and changes.

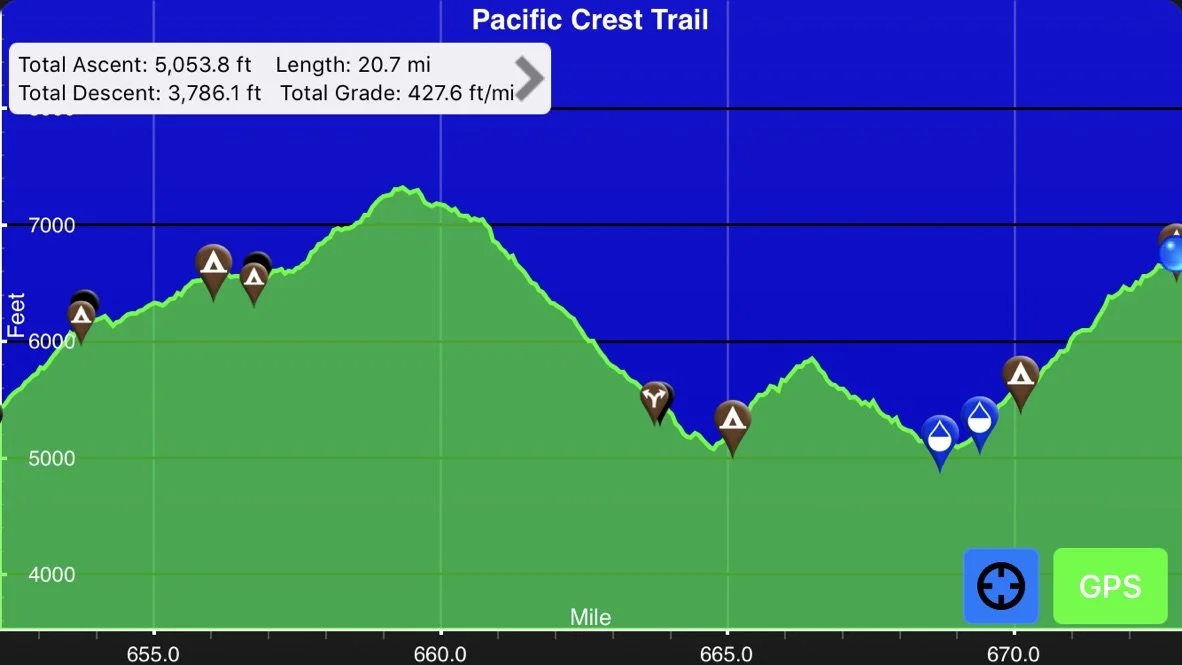

To track our mileage/location on the trail, Shawn and I used the Guthook’s Guides app, one of the most popular mapping apps for the PCT and other long distance trails, as well as many other trails throughout the U.S. and abroad. In addition to providing offline mapping, PCT mile location, current altitude, elevation ascent/descent, topography maps, and other useful mapping features, “Guthooks”, as its most often referred to on the trail, also includes information about water sources and tent sites, to which users can add comments with updated information about the source or site. It’s a pretty handy little tool.

I mention Guthooks mostly to credit that all of the mileage and elevation numbers below are based on the figures provided from this app. Mileage and elevation numbers may differ slightly if another map or GPS app, such as Halfmile, is used. The total trail miles indicated in the Guthook’s Guide app for this year was 2,652.6 miles, which is the figure I’ll use for the calculations below.

Fire Alternates and Other Reroutes

If you followed along with my blog, you’ll also remember me mentioning several fire alternates and reroutes. There were five significant reroutes/detours for us this year. I say “for us”, because depending on when you hit certain sections, some of the reroutes may not have been in place yet, particularly if they were due to fires. Those who traveled through certain sections earlier in the season may have been able to travel the official PCT before they were closed and rerouted due to wildfire. Others may have had even more reroutes than we had, or even had sections that were completely closed without an established alternative route, in which case they would have had to hitch forward to rejoin the trail where possible. As we hiked northward on the trail, there were also sections that were closed ahead of us that – fortunately – reopened before we arrived. All this to say, everyone’s journey up the trail tends to be slightly different depending on when they hit certain areas. Because wildfires seem to be the new normal in the west, I suspect this will be commonplace each year for the PCT. It is a living trail, always changing.

The five reroutes that we encountered included one fire alternate from a past fire, one endangered wildlife detour, and three alternate trails established due to current fires on or near the PCT.

The first fire alternate was just before Idyllwild, early into our adventure in Southern California, less than 200 miles into the trail. While it is due to a fire that occurred several years ago, the trail remains closed because the burn area is still too dangerous to travel through. The reroute involved a long climb and descent, but the scenery was great and the climb into the mountains was a nice change of pace from the desert landscape.

The second detour we encountered was also in Southern California, an endangered species detour for the endangered Mountain Yellow Frog that lives in the area. This detour, which includes a long section of road walking and some alternate trails, has been in place for many years and at some point the PCTA should probably consider creating a new route for the PCT through this region since the frog status doesn’t appear to be changing. Maybe they are waiting for the frog to bulk up its numbers and be removed from the endangered species list. May be a while. Ribbit, ribbit.

The remainder of our three reroutes were in Washington, all due to wildfires that were either on or near the PCT. Washington, which we generally associate with buckets of rain, was the last place we expected to have wildfire problems. We were wrong. Luckily, alternate trail routes were established for each of the closures so we were able to maintain a continuous footpath all the way to Canada. Many of the alternate trails were quite stout, with steep climbs (really nothing new for Washington) and very overgrown sections, but the PCTA did a great job of making sure they were well marked and pretty easy to follow. We appreciated all of the effort that went into establishing the alternate routes.

Amazingly, after adding up our PCT miles and the alternate miles hiked, our total mileage came in at 2,654 miles even, astoundingly close to the Guthook Guide’s total mileage for the PCT: 2,652.6. Because the figures were so close, I used the total PCT mileage for the calculations of averages and such below. If I were to add in some of the significant mileage that we hiked to get to/from the PCT in some sections, as well as our roundtrip Mt Whitney summit mileage (not part of the PCT), our total mileage comes in closer to 2,700 miles, which doesn’t even include adding up minor trails and shortish road walks to get to/from the PCT, side trails we took to various points of interest along the trail – geysers, vistas, summits, lakes, etc, the many side trails we hiked to collect water, and all of the walking we did in town to take care of resupply and other town chores. I imagine if I’d added all this up, we’d probably have walked closer to 2,800 miles. However, again – all of the calculations below are based on only the official Guthooks PCT trail mileage of 2,652.6 miles.

Alright, now that all of that explanation is out of the way, I present, the numbers:

NERD STUFF

Some General Numbers

Total Trail Miles: 2,652.6

Start Date: 4/18/18

End Date: 9/10/18

Total Days: 146*

# of Zeros (rest days, no trail miles for the day): 19

# of Neros (<10 trail miles for the day): 14

*The total days includes all zeros and neros, the total number of days it took us from the Mexico border to the Canada border.

The only general note I’ll make here is about zeros. Nineteen rest days may sound like a lot or it may not sound like that many. To be honest, I’m not sure where it stacks up against the full host of hikers. I’ve heard of hikers taking less than ten full rest days, and I’ve read of hikers that have taken thirty or more. There is a website called Halfway Anywhere that compiles a survey each year from every hiker willing to take it. The survey compiles averages of many of the data points I mention here, as well as many many others, and information about trail town stops and resupply that is both interesting to those that have already done the hike and useful to those that are planning for a future hike. Shawn and I have already completed the survey and it will be interesting to read the full results when they are made available once the hiking season is over. For now, I’ll just mention that the average number of zeros taken in 2017, according to the Halfway Anywhere survey, was 18 days. So, we are right around average. You can see the rest of the 2017 stats they compiled here. I’ll also post the results of the 2018 survey after it’s been compiled.

Our Pace

Total # of Days on Trail: 146

Total # of Miles: 2,652.6

Total Average Miles/Day: 18.2*

*this figure is an average of the miles per day and includes all zero days. Simply 2,652.6 miles divided by 146 days. The average without zero days included is 20.9 miles/day, but that figure is pretty much worthless. If we didn’t take any rest days at all, there is probably a decent chance we wouldn’t even finish. The body needs some rest. Figures below also include the zero/rest days.

Halfway Point: 1,326.3 miles

# of days to hike the first half of trail: 88

# of days to hike the second half of trail: 58

average mileage/day first half: 15.1 miles/day

average mileage/day second half: 22.9 miles/day

To say we picked up the pace in the second half would be an understatement. This isn’t to say that we were slacking during the first half. The first half of the PCT (heading northbound) includes both the desert and the Sierra, two terrains that require some extra time. Starting out on the trail, we – as with other hikers – also took more time to sort out the aches and pains of a thru hike… including a lot of foot pain for me – all of which result in typically taking more zeros and neros in the beginning so you don’t overdo it. By the time you near the end of the Sierras, assuming any major pains/aches/injuries have been sorted out, the body is physically and mentally prepared to handle more mileage each day, and the terrain also begins to lend itself to putting in more miles. While Northern California certainly still has plenty of climbing, Oregon is relatively mellow compared to other sections of the trail and you can put in a lot more miles/day.

After some mosquito misery through Yosemite, we ended up taking our longest rest period in South Lake Tahoe, hiking in on a Sunday morning and not leaving until Thursday morning. Leaving SLT on July 5th, we knew we needed to boogie if we wanted to make it to PCT days in Cascade Locks (at the border of Oregon/Washington) by August 17th and finish the trail by early to mid-September, hopefully before Washington was into full precipitation mode – particularly snow. We hitched into South Lake Tahoe from mile 1090.0 on Day 75 on the trail, our average at this point only 14.5 miles/day. Leaving South Lake Tahoe on Day 79, we would reach the Oregon border, 601.7 miles north of SLT, on Day 104, 25 days after leaving South Lake Tahoe. As a reference, our first 600 miles on the trail took 42 days. So yeah, we were definitely picking up the pace. We were also taking far fewer zeros, taking only one full zero in the over 600 miles between South Lake Tahoe and Oregon.

By the end, after covering 2,652.6 miles in 146 days, our average came in at 18.2 miles/day, which – coincidentally – was the exact average miles/day hiked by PCT thru-hike finishers in 2017 according to the Halfway Anywhere survey.

By State

California

Start Mile: 0.0, End Mile: 1691.7

Total Miles: 1691.7

Days in CA: 104

Number of Zeros: 14

Number of Neros: 11

Average Daily Mileage (all CA): 16.2 miles/day

Southern California

Total Miles: 566.5

Total Days: 40

Total Ascent: 95,290.7 ft

Total Descent: 94,359.9 ft

Average Daily Mileage: 14.2 miles/day

Sierra/Central California

Total Miles: 525.8

Total Days: 39

Total Ascent: 98.671.9 ft.

Total Descent: 95,089.6 ft.

Average Daily Mileage: 13.4 miles/day

Northern California

Total Miles: 599.4

Total Days: 25

Total Ascent: 102,558.1 ft

Total Descent: 103,911.4 ft

Average Daily Mileage: 23.97 miles/day

Oregon

Start Mile: 1691.7, End Mile: 2147.0

Total Miles: 455.4

Days in OR: 21

Number of Zeros: 5

Number of Neros: 2

Average Daily Mileage: 21.6

Total Ascent: 63,060 ft.

Total Descent: 69,058.1 ft.

While our total number of days in the state of Oregon was 21, this actually includes five zeros toward the beginning and end of the state for long resupply and rest stops in Ashland and Cascade Locks. A far more representative look at our time in Oregon would be our distance and time spent hiking between Ashland and Cascade Locks, a distance of 428.3 miles, which we covered in 14 days, for an average of 30.6 miles/day. This average was helped along by the fact that we did a 50 mile challenge in Oregon, hiking 51.3 miles from Ollalie Lake to Timberline Lodge in one day.

While many characterize Oregon as “flat”, I definitely wouldn’t call it flat, the PCT is almost continuously ascending and descending, with few truly flat sections through the journey. This said, the climbs in Oregon are far more mellow than most of what we found in California and Washington, and often allowed us to continue along at a good pace.

Washington

Start Mile: 2147.1, End Mile: 2652.6

Total Miles: 505.5mi

Days in WA: 21

Number of Zeros: 0

Number of Neros: 1

Average Daily Mileage: 24.1

Total Ascent: 102,087.6 ft

Total Descent: 97,916.7 ft

As you can see, we didn’t take a lot of rest in Washington. Entering Washington on August 21st, we were looking forward to the Cascades, but also anxious to move relatively quickly through the state, wanting to get through Washington before weather arrived. As it was, we did pretty good, only having 3-4 partial days of rain throughout the entire state. Washington was definitely the most stout section of the trip, with more elevation gain and loss than even the Sierra. The alternates actually had even more elevation gain than the official PCT sections that we missed, so the total ascent was likely to be closer to 108,000 or so, a crazy amount of climbing over 500 miles. This said, Washington also offered some of the most spectacular views, so while the work was hard, the reward was sweet.

Trail Towns and Resupply

# of trail towns/stops visited: 42

# of towns/stops where we purchased resupply food in town: 21

# of towns/stops where we picked up a box with our resupply: 11

CALIFORNIA

1- Lake Morena

2- Mt Laguna

3- Julian

4- Warner Springs

5- Idyllwild

6- Big Bear Lake

7- Wrightwood

8- Acton KOA

9- Agua Dulce

10- Casa de Luna

11- Wee Ville Market

12- Tehatchapi

13- Lake Isabella

14- Kennedy Meadows South

15- Bishop

16- Mammoth Lakes

17- Kennedy Meadows North

18- South Lake Tahoe

19- Donner Pass

20- Sierra City

21- Belden/Caribou Crossroads

22- Chester

23- Burney Mountain Guest Ranch

24- Burney Falls Visitor Center

25- Mount Shasta

26- Etna

27- Seiad Valley

OREGON

28- Ashland

29- Mazama Village

30- Shelter Cove

31-Big Lake Youth Camp

32- Ollalie Lake

33-Timberline Lodge

34- Cascade Locks

35- Portland

36- Hood River

WASHINGTON

37- Trout Lake

38- White Pass

39- Snoqualmie Pass

40- Stevens Pass

41- Holden

42- Stehekin

For the first figure above, “trail towns/stops” encompasses cities, towns, significant campgrounds, major visitor centers (Burney Falls), lodges (Timberline), and lake villages/vacation areas. Some of these places we stopped through for only an hour or less (usually for a snack, meal, or to visit an attraction) and some we spent several days.

At 21 of these stops, we purchased our resupply at a grocery store or small convenience store. These stops are marked above in blue. The only place of those listed that we had a somewhat difficult time resupplying was probably Caribou Crossroads, a small campground outside of Belden in Northern California. The selection here was fairly slim, though it was doable, especially since our next stop in Chester was only two days away. If I did it all again, I’d likely still buy my resupply at the general store in Belden or at Caribou Crossroads, mostly because – again – it’s only a couple days until a bigger resupply stop.

For 11 of our resupplies, we picked up boxes that we had mailed or that others had mailed us. Of those places listed in red, there are really only four places that I feel we absolutely needed a box. The places I would absolutely mail a box include Sierra City (Northern CA), Mazama Village (OR), Stevens Pass (WA), and Stehekin (WA), all due to very little selection at the very small stores at these sites. I was fairly surprised by how great/large the selection was at the other towns/stops highlighted in red, even when the shop available may have been quite small. For example, Warner Springs has always been listed as a place where you absolutely need to send a box; however, this year we found that the resource center had set up a little hiker shop and had a really great selection of resupply items. We definitely could have done our resupply from what was available there. Additionally, Kennedy Meadows North, the Burney Falls Guest Ranch, Shelter Cove, and White Pass also had only very small convenient stores or gas stations, but an excellent selection of goods that really catered to the hiker traffic that they received. Etna and Snoqualmie Pass had full grocery stores. We had never planned to send ourselves a box in Etna, but had extra food in a box sent to us in Sierra City, so mailed it ahead.

Catching our Zzz’s

# of nights in tent/outdoor enclosure: 106

# of nights cowboy camped: 3

# of nights indoors – hotel/hostel/AirBnB/trail angel home, etc.: 37

For the first figure above, outdoor enclosure basically refers to two nights that we slept in large tents that accommodated many people. We did this twice at the homes of trail angels, including Scout and Frodo’s in San Diego, the night before we started the trail, and at Hiker Heaven in Agua Dulce. All of the other nights just refer to sleeping in our own tent. Our little trail home ❤️

We cowboy camped only three nights. Some people never cowboy camp and many people cowboy camp far far more than this. Mostly, we don’t like the idea of any bugs flying around us when we are trying to sleep and would rather just set up our tent so we don’t have to think about this. This said, our three cowboy camping nights are all very special to me, with great memories attached.

Our first night cowboy camping was on a wind farm six miles before Tehatchapi. The wind was so strong, I thought we’d never find anywhere to camp, but we found a giant bush where the wind was completely blocked on one side. While LOL set up her tent, Squishy, Shawn, and I lined up our sleeping bags in a neat little row, blocked from the wind and snugger than bugs in a rug.

The second time Shawn and I cowboy camped was with a few other hikers a couple days north of Sierra City. Along with Flo, Baby Face, and Cap, we set up our mats and sleeping bags on a large ledge overlooking the mountains and woke up for front row seats to an amazing sunrise the next morning, along with coffee compliments of Flo. It was one of the best mornings on trail.

Our third and final cowboy camping experience was in Oregon, the night that we finished our epic 51.3 mile day from Ollalie Lake to Timberline Lodge. As it was nearing 12:30am when we arrived at the tent area near Timberline Lodge, we didn’t want to make too much noise setting our stuff up (or looking for a flat enough space for a tent), so instead quickly found a spot that was just good enough for cowboy camping. We were also too tired to care too much, so set up quickly and were soon fast asleep. This experience was mostly memorable because of the epic number of miles we’d pushed that day.

Shoes

pairs of shoes (Shawn): 5

pairs of shoes (Kate): 6

longest distance on a single pair of shoes (Shawn): 813 miles

longest distance on a single pair of shoes (Kate): 596 miles

My trail shoes included one pair of Brooks Cascades, four pairs of Altra Timps, and one pair of Altra Superiors. Two of these shoes were terrible for me; you can probably guess which ones. Shoes are a big deal on the trail. If you don’t have ones your feet like, you are gong to find out pretty quickly. The number of foot and leg ailments that sideline hikers in the first weeks and months is amazing – from your toes to your hips, there is a lot that can go wrong. While there are plenty of overuse and other injuries that don’t stem from footwear, there are also plenty that do. I quickly learned that even though a particular pair of shoes may be fine for a day hike or even a week long hike, they may not work for a thru hike, where you’re generally hiking 15-30 miles/day.

My feet were pretty dorked out when I started. Having read and researched all kinds of footwear suggestions for a thru-hike, I started in the Brook Cascades, Superfeet insoles, two socks on each foot – Injinji toe socks and Darn Tough hiking socks – a combination that was supposed to prevent blisters and wick away moisture, and laces tied in a particular way to ensure heal lock. In short, my foot/shoe system had a lot going on. Too much.

Breaks included lots of foot care.

Soon enough, I was getting some blisters – between my toes. I ditched the toe socks. Worthless. Despite feeling like I had plenty of room in my toe box, several of my toes started going numb, and pain radiated from the second and third toes up to the center of the top of my feet. On both feet. I started barely tying my shoes, leaving them as loose as possible, hoping to alleviate the pain in the top of my feet. Who needs laces? Worthless. On a particularly painful day on the trail, I sat down and took the Superfeet insoles out of my shoes, continuing the hike without insoles at all, hoping the extra space in my shoes would help. Who needs insoles? Worthless. At Big Bear Lake (mile 266.1), I picked up a box from my mom with my original shoe insoles. My pain did not improve. All of my toes were numb. By the time we got to Wrightwood (mile 369.4), I was removing my shoes as soon as possible. Who needs shoes!?!

In Wrightwood, I picked up another box from my mom – this time with a pair of Altra Timps that I’d had at home. I hadn’t been able to test out the Timps as much as I would have liked before leaving, so had gone with the Cascades. Now it was time to try the Timps again. The Timps were zero drop, and having not walked around extensively in zero drop shoes, I was somewhat worried that they would cause other ankle/shin/leg issues. Thankfully, they didn’t. And, they were super wide, which is apparently exactly what my feet wanted, because soon enough the pain that had once radiated from my toes to the top of my foot was no more. All of my toes were still numb, but this was not painful and I grew used to it. I didn’t even think about it when I was hiking. It seemed that this was caused by my first set of shoes, and now that the numbness had set in, it wasn’t likely to go away until I wasn’t walking all day every day. Who needs toes? Worthless!

All joking aside though, the Altra Timps were a godsend. They completely saved my hike. There had been times I wasn’t sure I’d even be able to make it through the desert in so much pain all the time, let alone finish the entire trail. Finally, with the Timps, I was no longer in pain every mile. Life was great! The Timps became my go-to shoes and each time it was time for a new pair, I got the same ones. Don’t mess with a good thing.

Unfortunately, for 200 very uncomfortable miles, I did mess with a good thing. After a ridiculous snafu with Running Warehouse in which they attempted – and failed – to have new Timps mailed to me three times in Mount Shasta, I ended up buying a pair of the Altra Superiors at a local outdoor store which, unfortunately, did not carry the Timps. I mistakenly thought the Superiors were also a high cushion shoe, however they turned out to be Altra’s lowest cushion trail shoe and I quickly felt this with every step. After only a few days in the shoes, as soon as I got cell service, I ordered new Timps to be sent to the next possible trail town I could get them: Ashland. Don’t mess with a good thing.

Shawn’s go-to shoes for the entire trail were the Lone Peak 3.5, which worked well for him. Like me, he had about a 200 mile section during which he also – mistakenly – tried to use different shoes. He’d had a pair of Salewa Speed Ascent shoes at home and figured, instead of buying another new pair of shoes, he’d just use a pair he already owned. (Cue sinister laughing). He quickly found that these were not going to work for his thru-hiking feet. Again, fine for a day hike or maybe even a week, but you’re hiking a lot more miles a day, every day, when you’re thru-hiking. He abandoned the Salewas as soon as possible for another pair of Lone Peaks. DON’T MESS WITH A GOOD THING!

Shawn also stretched his shoe use much longer than I did. Already scared of having more foot or leg issues, I wasn’t too keen on taking my shoes past 500 miles, already after the point at which you could tell the midsoles were worn down enough to need a new pair. I stretched on of my pairs to just under 600 miles, but Shawn stretched one of his to over 800 miles and could definitely feel it in his feet and legs. He was very happy when he finally picked up a new pair.

Number of Numb Toes

Kate: 10

Shawn: .5

As mentioned above in the shoe section, I had some issues with numb toes on the trail. This started pretty early on in the desert. At Hiker Heaven (around mile 450), I mentioned this to volunteer that had thru-hiked the PCT last year. His name was Numbers. He said it was “Christmas toe”, because you don’t feel your toes ’til Christmas. Haaaa… Apparently numb toes are not super common, but also not that uncommon. There are plenty of people along the trail that get at least some toe numbness.

After Shawn had tried his little shoe switcheroo to the Salewas, he told me that the very tip of his big toes were going numb, right foot more than left. I looked at him with a blank stare. I hadn’t felt any of my toes since around mile 100. I informed him that he would be fine. (Cry smiley).

Now that we’ve been off the trail for over two weeks (hard to believe), how are our toes fairing? Shawn’s numbness is pretty much gone. Mine is definitely improving, but still there. The smallest two toes on each foot are back to feeling normal. The others still have quite a bit of numbness, but I can tell it’s been decreasing the longer we’re off the trail. Four down, six to go. I’ll keep my fingers crossed that toe sensation will be back to normal by Christmas. Maybe even Halloween, but let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

Weight Loss

Enough about shoes and toes. Let’s talk about the real numbers everyone wants to know about. How much weight did we lose?

Weight Loss (Shawn): ~29 lbs.

Weight Loss (Kate): ~22 lbs.

We both lost a fair bit of weight. If you go back through all our photos on the trail, you can see our weight loss as we make our way up the trail. Our faces much chubbier in those early photos. By the time we were into the Sierras, you could definitely see the change, and by the time we hit Washington people were suggesting places to go to eat as soon as we finished the trail.

I cringe when I look at this photo. I think we have extra chins.

To be fair, we were both probably the heaviest we’ve ever been when we started the trail, our world travels having not been so kind to our waistlines. As it was, I was already about 12-15 pounds heavier than what I would consider the “normal” weight my body settles at when I’m eating fairly healthfully and keeping active. Shawn was also about 18-ish pounds over his typical weight. So, we were packing some extra pounds at the beginning anyway. Actually not a bad idea when you start a thru-hike.

Start and finish. Definitely lost a few pounds – and joined the calf club.

I should also mention that these weight loss figures are somewhat approximate. I weighed myself just before we went to San Diego, but once we finished the trail, it was four or five days before I was able to get to a scale. I had likely already started gaining weight back during those days, so if anything, I probably lost a little more than 22 pounds. The same goes for Shawn.

Please send cheeseburgers.

I wish I had kept track of how many ramens, mash potatoes, Knorr rice and pasta sides and candy bars we ate, but it’s probably better that I didn’t. Our sugar intake was high, and – while this had no affect on our waistlines – only a dentist visit will reveal what cavities we may have. 😩 The most important question once we were off the trail: how long can we continue eating like garbage trucks before our bodies figure out we aren’t walking anymore? The answer is probably not long. Off the trail, we treated ourselves for a bit, but are slowly working our way back into healthy foods and normal portion sizes. So long, soda.

Would We Ever Do This Again?

As we neared the end of the trail – even by the time we got to Northern California and Oregon, it seemed that this question was being thrown around relatively frequently. Would you do another thru-hike? Our short answer was/is: absolutely not. But let me unpack this.

Forgive me in advance for this very un-PC comment, but I pretty specifically remember a conversation to this end with some other hikers at Caribou Crossroads (not quite halfway through Norther California), during which one hiker put it: “You’d have to be retarded to this again”. While we might not have used the same words, we definitely shared the feeling. Most people think we were out of our minds doing it once.

There are so many things we loved about the thru-hike – the scenery of the constantly changing landscapes, from the desert to the high Sierra mountains to the meadows to the forest to the magnificent Cascades. We loved the people – the entire trail community, from the hikers to the trail angels to those that provided trail magic and hitches. We loved visiting the trail towns – small mountain towns you would likely otherwise never even think to visit. To some extent, we also loved the challenge – ticking off the miles and hitting each new 100-mile marker. Even all the little things – I loved the sound of the dirt crunching beneath my feet. I loved the sound of the trickling streams we crossed. I loved the smell of the forest and that strange minty scent I noticed in some places in Washington when it rained. I liked the impromptu swims, finding giant mushrooms, eating wild berries growing along the trail, and running into hikers we hadn’t seen for hundreds of miles. There were some miserable moments, to be sure, but these would always fade away with a beautiful view, good sunset, warm meal, or sleeping bag snuggle. There were so many things I loved, that we loved.

But, there were also things that we didn’t love. Most of this boiled down to the nature of a thru-hike. The long national scenic trails are seasonal adventures. For the PCT, In order to get to the Canada border before the weather turns, you have to keep it moving. While there are many amazing things about the journey, at the end of the day, you still have to put the miles in. Sometimes more than you want. Sometimes you’d like to stop longer, take longer breaks, swim in another lake, linger at a good view. This isn’t to say we didn’t do any of this, we definitely did. But, the miles are always in the back of your mind. If we wanted to finish before Washington’s fall and even winter weather crept in, we had to boogie. This was the part that we didn’t like, or at least I didn’t like. When we needed to make it so many miles today to get so far tomorrow so we could get into town by this certain time the following day for enough time to resupply and get to whatever point by the next night… etc. Sure, we could have slowed down a bit and taken longer to finish the trail. There are still people out hiking the trail as I type this. But – you never know how long you have. You don’t know when the first snows will come, when the mountain passes will be blocked and you will be closed out from the Canada border. And, to some extent, you keep moving because – even though the adventure has been amazing – you are tired of walking. We were ready to be finished walking all day every day for a while.

Absolutely none of this is to say we didn’t enjoy it. We wouldn’t trade this experience for anything. It’s hard to put into words the ways it challenges you and changes you.

For us, at least for now, we also feel it was a once-in-a-lifetime experience. We don’t have any (current) desire to do a hike of this length again, as absolutely amazing as it was. However, it did change our perspective on what a “long” hike is. There are certainly some 500ish mile, one-month-ish , hikes out there that we would love to do some day. Long hikes both home and abroad. But likely not quite as long as the PCT.

Who knows though? We have heard that some hikers know even before halfway through their first thru hike that they will do another one. Other hikers, even while completely enjoying most of the experience (as ourselves), say that – during their first thru-hike, they had no interest in doing another one ever again. Knew it would be a one-and-done type of adventure. Only to, in the weeks and months after the experience has ended, find themselves missing it, and eventually find themselves on another long trail once again. This reminded me of racing Ironman. There comes a point during the race – sometimes several points – where you think to yourself, why in the hell am I doing this? This is terrible. This is so stupid. I’m never doing this again. Only to find yourself online less than two weeks later, frantically signing up for another one before registration is full. You’ve got the bug…

In the mountain climbing world, they say you must have a bad memory to be a mountaineer. To release yourselves to the rigors of the mountains time and time again, you must be very forgetful of some of your past experiences. I think this must be true of all challenges worth taking. There are times that are miserable, times you beg yourself to remember the misery of the moment so that you don’t do it again. But as time goes, any bad memories fade and all you can remember is the adventure, the way it made you feel alive. There may or may not be another 2,000+ mile hike in our future, but there will certainly be more trails, more challenges, more adventures.

Until then, I will keep you posted when I can feel my toes again 🙂